- Guns, Germs and Steel – Jared Diamond

- Why Nations Fail – Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson

- The Bottom Billion – Paul Collier

- The Anti-Politics Machine – James Ferguson

- Peaceland – Severine Autesserre

- Sapiens – Yuval Noah Harari

- The Better Angels of Our Nature – Steven Pinker

- My Friend the Mercenary – James Brabazon

- Thinking Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

- The Black Swan – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

- The Undoing Project – Michael Lewis

- Seeing Like a State – James Scott

- States and Power in Africa – Jeffrey Herbst

- The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming – David Wallace-Wells

- Homo Deus – Yuval Noah Harari

Brief synopses and commentaries of these books are provided

below. I plan to update this list as and when I read other books worthy of a

mention. I hope you find it useful!

Development

Guns, Germs and Steel – Jared Diamond & Why Nations Fail – Daron Acemoglu & James Robinson

What is the most important geographic and historical fact of

human history?

and subsequent dominance of Europeans in the modern world. If this seems short-sighted and Euro-centric, consider for a moment the sheer scale of the European colonial project. In North America, British colonialists bullied and forcibly removed Native Americans; in Latin America, Spanish conquistadors eviscerated indigenous populations via unfamiliar weaponry and disease; in Africa, an entire continent was divided and divvied up by French, British, Belgian and German colonialists with breath-taking indifference; and in Australia, aboriginal Australians were literally exterminated by the British colonial regime. In each of these places, European colonialists imposed their language, religion, technology and institutions, almost all of which have persisted in some way up to the present day.

These facts give rise to one of the Really Big Questions of

Development Economics: why did Europeans come to dominate the globe, and not

Africans, Native Americans or Aboriginal Australians?

Until not long ago, a fairly common and uncontroversial

response to this question would be to appeal to Europeans greater intelligence,

or their stronger work-ethic instilled by their Judeo-Christian values. According

to Diamond, the pervasiveness of this view was not due to there being any

evidence that either of these things were true (there wasn’t), but

because Economists, Historians and Geographers had collectively

failed to put forward a convincing alternative explanation.

This changed with his publication of Guns, Germs & Steel

in 1997. In it, he put forward a new explanation that emphasised the importance

of historic geographic and ecological endowments in determining a nation’s

wealth – not the underlying characteristics of its people.

For example, people in areas with an historic abundance of

domesticable animals such as cows, oxen and pigs were able to transition from a

hunter-gatherer to an agrarian society more quickly. Control of crops and

livestock generated food surpluses, enabling people to specialise in activities

other than subsistence farming. Increased specialisation brought about

additional technological advancements, enabling early societies to support

ever-larger populations. This, in turn, sufficiently incentivised the build-up

of primitive state apparatus – a crucial precursor to modern industrial

development.

Despite significant fanfare when the book was published,

Guns, Germs and Steel left a number of unanswered questions. Geography is

remarkably unchanging: yet human history is characterised by the rise and fall of

different civilisations. The Aksum, The Angkor and The Mayans were all once

among the most advanced societies of their time, yet their descendants now all

reside in countries towards the bottom of the global income distribution. Why

is this? The geography of these places has not changed in thousands of years; there must be another piece of the puzzle.

Acemoglu & Robinson largely pick up the baton of this

question in Why Nations Fail. In it, they argue that institutions – the

rules of the game of society – are the most crucial determinant of a country’s

success. Institutions are deep-rooted but not immovable, which allows for the

numerous ‘Reversal of Fortunes’ that punctuate human history. It

also explains how two neighbouring cities with identical geographies and the same name –

Nogales – can have such divergent economic, health and education outcomes

today. The answer, they argue, lies in the the different institutional quality of the different countries they inhabit: Nogales Sonara lies in Mexico; Nogales Arizona lies in the United States.

Guns, Germs & Steel and Why Nations Fail are often

viewed as two books antithetical to each other: you are either in the geography

camp, or the institutions camp, but not in both. I think this is wrong – both

books contain important insights and much can be gained from a synthesis of the

two. For this reason, I include them together in my list.

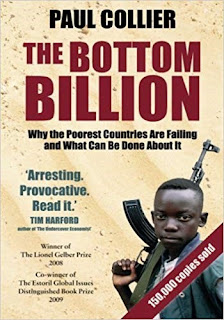

The Bottom Billion – Paul Collier

I first read The Bottom Billion when I was 17 years old on a

voluntourism trip to Bolivia (I know). At the risk of sounding sentimental, this was the first Economics book I ever read in the first developing country I ever visited – at a time when I was still planning to study History at University. Reading this book in this setting made me confront questions I hadn’t given much thought to before: why are some countries so much poorer than other? And is there anything we can do about it? By and large, these remain the questions I find most interesting today.

Collier has his own answers to these questions which he lays

out thematically in separate chapters. He argues that countries are poor

because they fall into one or more of four development ‘traps’:

the conflict trap, the natural resource trap, being landlocked with

bad neighbours and the bad governance trap. Once there, a confluence of

self-reinforcing factors makes escape especially difficult. The net result of

this is a ‘Bottom Billion’ – a billion or so people that are poor; and stuck in

countries that are going nowhere.

To remedy this, Collier proposes four solutions. First, the

aid industry should take on more risk and increasingly concentrate itself in

the most difficult and desperate environments. Second, appropriate military

interventions (such as the British in Sierra Leone) should be encouraged,

particularly to guarantee democratic governments against coups. Third,

international charters are needed to encourage good governance and provide

prototypes. Finally, trade policy in both developed and developing countries

needs to encourage free trade and give preferential access to Bottom Billion

exports.

Did this book save me from being a loquacious Arts student?

Possibly. Are the methodologies Collier uses now out-dated? Probably. Has he

said some pretty stupid stuff since? Definitely. But is this book still one of

the most accessible and engaging introductions to Development Economics?

Absolutely. Read it!

The Anti-Politics Machine – James Ferguson

The Anti-Politics Machine is an excruciating post-mortem of

an almost unbelievably ill-conceived World Bank project that took place in Lesotho from 1975-84. The project, dubbed the Thaba-Tseka Development project, sought to ‘modernise’ the Basotho economy by encouraging a switch to cash crops, introducing sustainable livestock practices and building roads to connect rural farmers to markets. The project was woefully unsuccessful: by 1984, crop output remained low, new livestock practices were completely ignored and agricultural exports remained largely unchanged. On top of this, the project’s tree-planting project was sabotaged, fences delineating the project area were torn up, and a project manager’s car was set on fire.

How did it go so wrong? Ferguson argues that it all stemmed

from a fundamental misconception of the Basotho economy, epitomised by the project’s

laughably inaccurate inception report. The report portrays Lesotho as a

backwards, isolated, and predominantly agrarian society whose development had

been thwarted by lack of reform efforts by both colonial and post-independence

leaders.

About 5 minutes of research shows this to be completely false. Lesotho was not, and has never been, a predominantly agrarian society:

at the time the report was written, less than 10% of household income came from

farming. Instead, over 60% of Basotho men were employed in industrial jobs

in neighbouring South Africa – which formed by far the biggest contribution to

Basotho GDP. This reliance meant that Lesotho was – and always had been – deeply

embedded in the regional economy, and not the aboriginal ‘island’ economy the

report sought to portray.

This misrepresentation was no accident. A truthful portrayal

of Lesotho’s situation would reveal that nearly all determinants of economic

life in Lesotho relied on factors outside the nation’s borders. However,

such a representation would leave no role for the World Bank. Instead, by

emphasising the importance of agriculture and obsessing over government policy

as the most crucial variable in Lesotho’s success, World Bank economists had

carved a role for themselves as indispensable gatekeepers in Lesotho’s road to

prosperity.

I find this book so interesting not least because I see

similar dynamics at play in Zanzibar. Here, ‘underdevelopment’ often seems

attributed to people doing things wrong – things that more learned, or

more capable people simply would not do. Accordingly, government non-compliance

is put down to a lack of understanding or capacity, rather as a strategic

reaction by individual agents with wide-ranging and often incongruous

incentives. The result is to fundamentally misconstrue the state as an

apolitical entity – an ‘Anti-Politics Machine’. This reduces ‘development’ from

a social and political problem to a largely technical problem – one in which

consultancies, aid agencies and international organisations are perfectly

poised to help solve.

Peaceland – Severine Autesserre

Why do aid and peace interventions so often go awry? James

Ferguson provides one answer to this question; Severine Autesserre provides another. Peacekeepers, aid workers and diplomats occupy a different social space to the places in which they work – a space she dubs ‘Peaceland’. This space is characterised by its own distinct beliefs, behaviours and rituals. Examples of these include socialising exclusively in expat circles, not speaking the local dialect, upping sticks every few years, favouring technical know-how over regional expertise and abiding by unnecessarily stringent security procedures. These practices often seem innocuous at face value – but together they create a distinct sense of ‘otherness’ that hinders contextual understanding and often exacerbates tensions between interveners and local populations.

I read this whilst in ‘Aidland’ in Zanzibar – not quite the

same as ‘Peaceland’, granted, but a social space with striking resemblances. I

read it with a mixture of intrigue and embarrassment as I realised I conformed

to almost all the stereotypes of the boujie aid worker in Tanzania: not

speaking Swahili ✔; drinking at the 6 Degrees and the Slow Leopard ✔; subsisting on a diet of sushi and Huel ✔.

I don’t think there’s a problem with this per se – but when it comes at the

expense of all other social and cultural engagements then it begins to produce the

consequences that Autesserre so expertly outlines.

Since reading Peaceland I’ve definitely tried harder to

escape the ex-pat bubble. I’ve joined a local football team; I’ve visited local

colleagues’ homes and invited them to my own; I’ve doubled-down on my shaky

Swahili. So yeh – I’m still a boujie aid worker – but at least now I’m trying

harder.

Sapiens – Yuval Noah Harari

I remember getting the District line from Earls Court in 2015 and

there being about 10 people in my carriage all with their noses in this book. While suit-clad commuters are hardly a representative sample, this book seemed to strike a chord with almost everyone: from University Professors to Love Island contestants. I think this is mostly to do with the book just being so damn readable: I remember buying this in Delhi airport and then having almost finished it by the time I touched down in Heathrow.

This is not marketed as a book about development, but in my

mind it’s about human development in the really, really long-run. In charting

the rise of the human race, Harari sets himself an even deeper question than

Diamond, Acemoglu & Robinson: not just why Europeans came to

dominate other humans, but why Homo Sapiens came to dominate

other species.

Harari’s answer to this question rests not on our ability to

stand upright, use tools or communicate via language, but on our unique ability

to believe in things which don’t really exist – that is, things with no

direct correspondence to the physical world. For example, chimpanzees are able

to tell each other if there is an eagle circling them overhead – a very real

phenomena in the physical world – but are unable to discuss abstract concepts

like God, democracy or monkey rights.

Humans, of course, can imagine these things – and our

capacity to do so enables our uniquely human ability to cooperate flexibly

and in large numbers. Chimpanzees are able to cooperate flexibly but not

in large numbers, as all cooperation must be underpinned by personal

relationships. This sets an upper limit on chimpanzee troops of about 150 members.

Ants and bees can cooperate in large numbers but not

flexibly. Their social relations are defined by their DNA – not by their

shared beliefs. For worker ants to rise up and overthrow their queen, this

would take millions of years of evolution. By contrast, humans in 18th

century France were able to transition from a monarchy to a democracy virtually

overnight, as their shared myths about the natural and just social order were

quickly and violently rewritten.

All human accomplishments can eventually be traced to this

ability for large-scale and flexible cooperation. The fruits of this are hard

to overstate: the ability to walk on the moon; to eradicate deadly disease; to

create weapons powerful enough to destroy civilisations. By the end, you are

left to marvel at our voyage from insignificant apes in the corner of East

Africa to the undisputed masters of Planet Earth. Very humbling indeed.

War & Conflict

The Better Angels of Our Nature – Steven Pinker

Like Sapiens, this was another book that littered bookshelves, conversations and coffee tables upon its release in 2011. Pinker’s central thesis is that – despite the seemingly incessant stream of bad news that fills our TV screens – the prevalence of violence has unambiguously declined throughout human history. This decrease has been universal in scope: wars have declined; genocides are less frequent; homicides have decreased; the acceptability of torture has fallen; sexual violence has decreased; even terrorism – so often perceived as the defining feature of the post-9/11 world – has remained at barely perceptible levels as far as the entire species is concerned.

Pinker identifies five historical forces that have facilitated

this decline. First, the rise of the modern nation-state has enabled the

monopolisation of the legitimate use of force, reducing the temptation for

individuals to enact extra-judicial revenge. Second, the forces of

globalisation have enabled the

trading of goods over longer distances, bringing distant societies

into contact with each other and making each, in the eyes of the other, “more

valuable alive than dead”. Third, women have become more emancipated in both

political and domestic spheres, and have tended to be more doveish in both their

voting patterns and social behaviour. Four, the rise in literacy, mobility and

mass media has led to the State being fundamentally reconceptualised as a protector

against violence to a guarantor of human rights. Finally, Pinker points to the

Escalation of Reason in exposing the sheer pointlessness of war and in reframing

violence as a problem to be solved rather than a contest to be won.

Of course, there is a lot to disagree with. I think his

basic argument is essentially correct – violence has declined over the

course of history, and any far-reaching historical, political or social theory

of human history has to somehow take this into account. However, what bothers

me about Pinker – and indeed the New Optimist crowd in general – is the sleight

of hand deployed in moving from the empirical claim that violence has

declined to the subjective claim that the world is now more secure.

It is perfectly consistent to claim that the world is both much less

violent and much less secure – and hence hardly the stuff to be celebrating.

For example, our success in stymying ancient forms of

violence does nothing to assure us against the relatively new threats

posed by nuclear war, environment degradation, artificial intelligence and

bio-hacking. If things go wrong now, they go really, really wrong – a

fact that Pinker largely dances past in his follow-up book, Enlightenment Now. This

makes me reluctant to join Pinker in his New Optimist camp – no matter how

compelling his argument in The Better Angels of Our Nature may be.

My Friend the Mercenary – James Brabazon

Brabazon, a war journalist who was the only person to film the LURD rebel group inside Liberia during the Second Liberian Civil War (1999 – 2003).

The first half of the memoir recounts Brabazon’s friendship

with Nick du Toit – a South African mercenary-cum-arms dealer who Brabazon

hires to be his bodyguard for his tour of Liberia. Together, the two make

contact with LURD rebels at the Guinean border and join them on their

subsequent march to Monrovia. Their journey is marred by severe illness,

near-impenetrable rainforest and frequent encounters with government soldiers –

some of which end in execution, torture and ritual cannibalism. Much like

Marlow’s journey to the Heart of Darkness, Brabazon’s journey to Monrovia reflects

a journey to the depths of the human

soul – and the depravity of what it’s capable of.

For all this vividness, Brabazon – to his credit –

frequently cautions against the stereotype of the blood-thirsty African rebel.

He makes an admirable attempt to form close bonds with the soldiers and allow their

personal stories to echo through his pages. In doing so, Brabazon helps

‘humanise’ the conflict, helping the reader appreciate the sheer depth of

circumstances that turns otherwise ordinary citizens into such desperate acts

of violence.

After the Liberian War ends, du Toit invites Brabazon to

film ‘regime change’ in Equatorial Guinea: an outrageous coup attempt financed

by extremely shady British establishment figures including Mark Thatcher,

Margaret Thatcher’s son. By an amazing fluke, Brabazon misses his flight to

Equatorial Guinea and is forced to watch on the news as the plot is uncovered

and defused. Du Toit gets arrested and accused of high treason, culminating to

a life sentence at Black Beach prison, notoriously known as the most brutal

prison in the world.

Brabazon began writing his memoir largely as a testimony to

his friend and former bodyguard, whom he safely assumed he would never see

again. However, in another extraordinary twist of fate, du Toit is released just

5 years into his sentence. This book concludes with the pairs’ rendezvous, with

du Toit recounting further gruesome tales of survival in Black Beach.

By the end of all this, you aren’t really sure what to make

of Brabazon. Despite his attempts otherwise, you can’t help but think that he is

perpetuating negative African stereotypes – at least in the minds of his more

lazy and prejudiced readers. He’s also a bit of a mercenary himself: barging

into conflict zones uninvited to harvest footage for his award-winning

documentaries. With this being said, Brabazon certainly has balls – what’s

more, his work undoubtedly shines a light on conflicts which may otherwise be forgotten.

Whatever the final judgment – I’d certainly like to go for a beer with him.

Risk, Uncertainty and Behavioural Economics

Thinking Fast and Slow – Daniel Kahneman

Fast and Slow chronicles the most famous findings of Danny Kahneman’s extraordinary research career. Along with Amos Tversky and Richard Thaler, Kahneman helped transform Behavioural Economics from an eccentric, nagging, but ultimately ignorable thorn in the side of mainstream Economic theory to one of the fast-growing and important sub-fields of Economics today.

For a large part, Behaviour Economics is concerned with how

humans make decisions. Before the subject came to be, orthodox economic theory

was built on the assumption of Rational Economic Man: the cool, calculating

machine that abided by several axioms of rational choice. Sure – Rational

Economics Man occasionally made mistakes, but these mistakes were so random and

infrequent that they could be safely ignored for the purpose theory and public

policy.

Behavioural Economics essentially took a sledgehammer to

this assumption by showing that, in many contexts, humans make predictable and

systematic mistakes. Rather than axioms of rational choice, humans are

instead governed by two ‘Systems’ of thought: a fast, emotional and instinctive

System 1 and a more cool-headed, deliberative and logical System 2. While

traditional Economics would have you believe that System 2 was always in

control, Kahneman and his collaborators showed that System 1 often intervened

automatically. This gave rise to many ‘biases’ – behaviour at odds with

textbook rationality. Examples of these include the halo effect, loss aversion,

confirmation bias and the narrative fallacy.

What I like so much about this book is that it’s peppered

with actual thought experiments to test your own susceptibility to System 1

thinking (I fell for almost all of them). My favourite of all these experiments

involves estimating the odds that a car from either a Blue Cab Company or a Green

Cab Company was involved in an accident. I won’t spoil the punchline here – but

needless to say this example bamboozled me then and still bamboozles me today.

I know what the right answer is; I know the mathematics to get to the right

answer; but for some reason my brain still screams at me the wrong answer. The

power of System 1 thinking!

The Black Swan – Nassim Nicholas Taleb

Next on this list is a book by loud-mouthed, Ferragamo-tie-hating,

former derivatives trader & Econ Twitter über-villain Nassim Nicholas Taleb – or NNT, as he often abbreviates. The book focuses on Black Swans – unpredictable, high impact events that we tend to ignore and downplay by applying simplistic explanations retrospectively. Examples of Black Swans include 9/11, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of the internet. These events dominate our world – yet by their very nature, were impossible to predict in advance.

former derivatives trader & Econ Twitter über-villain Nassim Nicholas Taleb – or NNT, as he often abbreviates. The book focuses on Black Swans – unpredictable, high impact events that we tend to ignore and downplay by applying simplistic explanations retrospectively. Examples of Black Swans include 9/11, the collapse of the Soviet Union and the rise of the internet. These events dominate our world – yet by their very nature, were impossible to predict in advance.

To cope with a world defined by these events, Taleb advocates

a number of strategies. First, forecasters are to be ignored – especially those

without Skin in The Game. Second, the Bell Curve – with its focus on

averages rather than extremes – should be abandoned, except in a few very

specific contexts (e.g. human height). Third, our entire epistemology must be

overhauled: focus should move from knowledge (the stuff that we know) towards anti-knowledge

(the stuff that we don’t). Fourth, we should become Anti-Fragile:

distributing our eggs across many baskets to ensure that no single event can

ruin us completely. Finally, we must make peace with the unavoidable chaotic of

the world and adopt a stoic, detached stance – like Buddhism, says Taleb, but

with a “F*** you!” to fate!

In making his case, Taleb takes us on a breath-taking voyage

through the history of scepticism and the philosophy of science and social

science. He devotes numerous pages eulogising the early purveyors of

anti-knowledge and unpredictability: David Hume, Karl Popper and Benoit

Mandelbrot. He also makes sure to slag off those who systematically

over-simplify and under-estimate the world – ‘fragilistas’, as he calls them.

Into this category falls Karl Marx, Carl Gauss and even Plato – no one, it

seems, is safe from his arrogance or ire.

For all his bluster, NNT can certainly walk the walk. Each

time I read one of his books I come away viewing the world through different

lenses. Some of his advice is undoubtedly wise (become Anti-Fragile; ignore

those without Skin in The Game); some of his advice is, well, eccentric (never

run for a train, never read the newspaper and never drink anything from the

past 4,000 years). He’s like a controversial uncle around the family Christmas

table: rude, obnoxious, but undoubtedly entertaining and at times mesmerising.

His online presence is also legendary: from posting videos of his deadlift sets

on Facebook to calling Steven Pinker a fraud on Twitter, NNT is truly the gift

that keeps on giving.

The Undoing Project – Michael Lewis

They were different in every way. But both were obsessed with the human mind – and both happened to be geniuses.

So reads the blurb of The Undoing Project – the remarkable

biography of Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky. In chronicling their lives and

careers, the book is ostensibly about the founding of Behavioural Economics – but

it’s also about so much more. It’s a tale of two types of genius: one

arrogant, unfettered and seemingly unlimited; the other measured, perfectionist

and wracked with self-doubt. It’s a tale of a young Jewish boy in Nazi-occupied

Paris, and his death-defying escape to Israel. It’s a tale of human fallibility;

and our inability or unwillingness to accept this fact. It’s a tale of

unorthodoxy triumphing over conventional wisdom. It’s a tale of friendship and

the love, laughter and envy that this encompasses. It’s a book about human

happiness, and how it can be misunderstood. Finally, it’s a tale of the

finitude of human life, and a reminder that even the brightest stars eventually

fade away.

Of all the books on this list, this one is undoubtedly the

most moving. Read it!

Political Science

Seeing Like a State – James Scott

For Scott, the central project of the State boils down

to one thing: legibility. Any substantial state intervention in society – vaccinating a population, mobilising labour, enforcing sanitation standards, taxing people and their property, conducting literacy campaigns, catching criminals or conscripting soldiers – requires the invention of units that are visible.

to one thing: legibility. Any substantial state intervention in society – vaccinating a population, mobilising labour, enforcing sanitation standards, taxing people and their property, conducting literacy campaigns, catching criminals or conscripting soldiers – requires the invention of units that are visible.

To do this, primitive states had to demarcate and

standardise a rich and varied tapestry of localised norms and social

structures. Surnames were invented to make individuals identifiable and their

lineage traceable through time. Standardised weights and measurements were

introduced to make regional goods commensurate, and to ensure that their

production could be monitored and taxed. Universal languages were imposed to ensure

disparate groups could be understood, educated and instructed. Entire cities

were built around perpendicular axis and geometric squares to ensure their

populations could be counted, regulated, spied upon and organised.

This ‘high modernist’ planning gives States’ the unparalleled

ability to move and manipulate groups of people en masse, but it is not

without its costs. It becomes risky when it supersedes local practices that

have adapted to local contexts over several centuries. And it becomes downright

dangerous when it is combined with an authoritarian state and a weak civil

society.

Take, for example, the ‘ujamaa’ project of Julius Nyerere’s

Tanzania. Taking the reins of power in 1964, Nyerere was one of the foremost

champions of the high modernist belief that it was the state – and the state

alone – that knew how to organise a more satisfactory, rational and productive

life for its citizens. He embarked on a compulsory villagization programme:

smallholder farmers were forcibly relocated to massive collective farms that

could be readily monitored and dictated from above. The results were

disastrous: agricultural output collapsed and Tanzania became heavily reliant

on food imports between 1973-1975. The blunt, unvaried and clinical logic of

the State was no match for the nuanced local practices that had centuries of

adaptation to fall back on.

This book has notable overlaps with two others on this list:

The Anti-Politics Machine and The Black Swan. Like Scott, both Ferguson and

Taleb caution against blanketing a highly complex social world with crude, abstracted

and over-simplified explanations. Of course, as practitioners and students of

social science, it’s our job to understand this world – something

which can’t be done without simplification and abstraction. So how should we

proceed? Scott gives four pieces of advice: first, take small steps:

intervene moderately, stand back, observe, and then plan the next small move.

Second, favour reversibility: prefer interventions that can easily be

undone if they turn out to be mistakes. Third, plan on surprises: choose

plans that allow the largest accommodation of the unseen. Finally, plan on human

inventiveness: always assume that those involved in the project will have or

develop insight to improve upon the design. I would add a final one: be humble

– acknowledge the limits of social science and that our world is often too

complex, chaotic and unpredictable for us to fully understand. But don’t let

that deter you from trying!

States and Power in Africa – Jeffrey Herbst

To answer this question, Herbst makes an exhilarating

journey through African pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial history. The answer begins, Herbst says, in the unique complexion of war in pre-colonial Africa. Unlike in Europe and Asia, pre-colonial wars of territorial conquest were extremely rare. The reason for this was two-fold: first, unlike in Europe, land was extremely abundant – by 1975, Africa had only reached the level of population density that occurred in Europe in 1500. Second, unlike in Asia, land was extremely cheap – the plough never reached Africa, meaning that even royal villages would move periodically as the soil became exhausted. This was in stark contrast to Asia – where the painstaking labour that went into constructing tiers of rice paddies meant that land was worth defending – and conquering.

journey through African pre-colonial, colonial, and post-colonial history. The answer begins, Herbst says, in the unique complexion of war in pre-colonial Africa. Unlike in Europe and Asia, pre-colonial wars of territorial conquest were extremely rare. The reason for this was two-fold: first, unlike in Europe, land was extremely abundant – by 1975, Africa had only reached the level of population density that occurred in Europe in 1500. Second, unlike in Asia, land was extremely cheap – the plough never reached Africa, meaning that even royal villages would move periodically as the soil became exhausted. This was in stark contrast to Asia – where the painstaking labour that went into constructing tiers of rice paddies meant that land was worth defending – and conquering.

This different dynamic of war had a profound impact on early

state formation. In Europe and Asia, the allure of territorial conquest

prompted elites to secure their borders and develop extensive tax frameworks –

both of which required them to develop close connections with the hinterland.

In Africa, by contrast, rural populations remained virtually uncaptured by the

state apparatus.

The next part of Herbst’s explanation charters the

transformation of the African state under colonial rule. Colonialism

effectively grouped together previously disparate and transient populations

into arbitrary geographic blocs. Despite this new cosmetic, European occupiers

generally chose not to enhance the reach of the state much beyond the centre.

Doing so was expensive – particularly due to Africans vast geography and lack of

navigable rivers – and hence did not show up favourably in the cold

cost-benefit calculus of colonial rule. The exception, of course, was if an

area was abundant in natural resources – which could be extracted and then

funnelled through the centre.

At independence, this urban bias was perpetuated by

inaugural elites for largely pragmatic reasons. Urban workers could strike,

riot or concoct a coup d’état; rural peasants, by contrast, were a lot less

threatening to the regime. As a result, surveillance and spending were

disproportionately biased towards the centre – again leaving the countryside

relatively uncaptured.

However, while elites had little incentive to tighten their

grip over rural populations, they had little incentive to let them go, either.

Doing so would relinquish some of their newly found power: not only would they

lose land, resources and (albeit limited) tax revenues, they would also lose credibility

in the international arena.

By 1950, the principal of state sovereignty had become a

virtually unassailable juridical norm. This can be traced to the horrors of

WWII and the partition of the Indian sub-continent, both of which made vivid

the human cost of boundary change and territorial ambition. The New World responded

by a near-universal embrace of the nation state. Irredentist movements were

almost always condemned and new organisation like the World Bank, the UN and

the IMF identified nation states as the only legitimate actors they would do

business with. To access this New World, African states had to remain unified: even

if it meant holding on to bizarre and incoherent blocs handed to them by

colonial rule.

What I like so much about Herbst’s argument is that it makes

modern-day aberrations like state failure and civil war a lot less mysterious.

When you consider that many African states are characterised by illogical borders,

uncaptured rural populations and disparate ethnic and linguistic groups, the

lack of effective policymaking hardly seems surprising. And when you consider

the immense role that war played in state formation in Europe and Asia – and

the bizarre way in which most African states came into being – then civil war

doesn’t seem like such a stupid thing.

Climate Change

The Uninhabitable Earth: Life After Warming – David Wallace-Wells

While the first half of the book outlines our likely

trajectory absent an urgent response, the second half explores how the human

condition may change in the face of impending disaster. How will climate change

mould our collective conscience and the stories we tell our children? How will our

political, economic and moral systems adapt in the face of unprecedented

upheaval? How will death, ecological disaster and economic collapse affect our

perception of the journey we’ve taken on Planet Earth?

This is not a cheery read. No punches are pulled in

outlining the enormity of the crisis we face. There are very few silver

linings. The book does not end in a flurry of optimism about human ingenuity

and technological progress – something I find morbidly refreshing.

Despite this, The Uninhabitable Earth really is essential

reading. Millions of people have already been killed by climate change – whether

via wildfires in California, flooding in Bangladesh or conflict in the Sahel.

The impacts of climate change in the next 100 years are going to be bad –

but there is a massive degree of scope in terms of how bad things will be. It matters

whether we heat the Earth by 2°C or 3°C. It matters whether

millions or billions of people die. Wilful ignorance of the risks is not a

morally defensible strategy. If, like me, you’re not versed in the current

scientific consensus, The Uninhabitable Earth is a great place to start.

Technology

Homo Deus – Yuval Harari

Homo Deus is the equally-hyped follow-up to Harari’s

ludicrously successful debut work, Sapiens. Sapiens ends with a wild prophesy: that Sapiens, via our scientific advancement, are cooking up the next epochal revolution – the technological revolution – that will overshadow the previous three (the cognitive, the agricultural and the scientific). Homo Deus is the full exploration of this prophesy.

ludicrously successful debut work, Sapiens. Sapiens ends with a wild prophesy: that Sapiens, via our scientific advancement, are cooking up the next epochal revolution – the technological revolution – that will overshadow the previous three (the cognitive, the agricultural and the scientific). Homo Deus is the full exploration of this prophesy.

Harari begins with a brief survey of human progress. Up

until now, human meaning and progress has been largely defined relative to an ongoing struggle

against the historic enemies of mankind: plague, famine and war. Now, for the

first time, these scourges are falling under our control. Diseases such as

smallpox, river blindness and polio have all but been eradicated. Famines have

become sensational, not routine. Major war has become seemingly obsolete.

As we elevate ourselves above beastly survival struggles,

Harari speculates that we will divert more time and energy towards upgrading

the base human condition. Indeed, this trend is already visible: we outsource

biological algorithms to our smartphones; we use aids to improve our hearing

and sight; we take anti-depressants to alter our brain chemistry; and we have plastic

surgery to makes us beautiful. Our ability to do this makes us already God-like,

at least by the standards of most of history. However, if we continue, even more God-like

abilities may be on the horizon: the ability to cheat death, customise embryos

or even create life itself.

However, just like the three revolutions that preceded it,

this revolution will come with a price. Sophisticated human upgrades will

likely only be available to those who can afford it. The implications this has

for global inequality may be unprecedented. Today, for the most part, the global superrich are

physiologically indistinguishable from the masses – we have the same size

brains, the same fleshy carcass and the same reliance on nutrients, water and

oxygen. What if this were no longer the case? What if the super-rich, via bodily upgrades, were able

to become faster, smarter and stronger than the rest? This is a scary prospect indeed – and one

which our current systems of politics, laws and ethics are not equipped to deal

with.

Things go from bad to worse. Even if we avoid this

threat and create a super-human future for everyone, we risk propelling

ourselves into a world devoid of any real meaning. How will we cope in a world

where any economic, political or cultural endeavour can be done by algorithms better than by ourselves? We will need a new religion to make sense of all this: the

powerful combination of science and humanism will not work in a world where the

sanctity of being Human has lost all meaning.

Homo Deus is, of course, extremely broad-brushed and speculative in its treatment of the future, placing it in a broader category of books that are seemingly in vogue at the minute. In my eyes, Homo Deus is the best of the bunch – with an honourable mention to Future Politics by Jamie Susskind, which narrowly misses out on this list.

Unlike other books I’ve read, Harari treads a careful line between starry-eyed optimism and doom-mongering fatalism – probably the most sensible stance, given both the scale and unpredictability of our technological charge. He also sees the bigger picture better than most – teasing out the implications of technological advancement on philosophical themes as broad as human experience, individualism, human emotion and consciousness. If you’re interested in where we might be headed – or simply in what it means to be human – this book is for you.

No comments:

Post a Comment